Let me say, right up front, I am a free jazz guy. I came to jazz via rock music, and most of my favorite jazz is loud and raw and screwy. That said, I have lately been involved in a collaborative writing project about free jazz that has forced me into parsing some of the differences between “true” free jazz, and a similar hybrid known as “spiritual jazz.”

Like all such genre distinctions, this one is arbitrary, subjective and almost imaginary.

In a general way, this particular branch of jazz emerges in the wake of Coltrane’s 1965 Impulse LP, A Love Supreme (which may be the last session Coltrane did before he began dreaming about Albert Ayler). Many other powerful forces were in the works then (cultural, political and musical), but the 33-minute title track, broken into three sections, built around a strong central pulse, was a kind of blueprint for much subsequent action. To these basics add an Afro-centric, Afro-futurist or interstellar motif, some exotic instrumentation if you like, female vocals or chants if you can, and, as the Aussies say, “Bob’s your uncle.” This is an overly simplistic recipe, natch, but you get the idea.

One of the most interesting things we discovered in our winnowing process was that many artists we reflexively think of as free jazz players, are actually closer to the spiritual bag. For instance, Farrell “Little Rock” Sanders, who can be a wild outside force as a sideman, has never cut a “true” free jazz LP as a leader. Even Sun Ra has precious few albums that don’t ultimately qualify as “spiritual” rather than “free.” And many of the major free jazz giants have cut albums that are definitely gusts of spirit-breath. New Grass, anyone?

Anyway, spiritual jazz, has become a super popular and collectible sub-genre over the last quarter century (spurred largely by UK reissue labels) and there are still a lot of real obscurities out there to discover. There are also some major artists and musical organizations who were under-documented in their day. This list includes the Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, a Los Angeles-based band formed and led by pianist/composer/teacher/agitator, Horace Tapscott, who died in 1999. The name of the band, by the way, has more to do with the idea of saving ideas from the Great Flood than it does as a reference to Le Sony’r Ra.

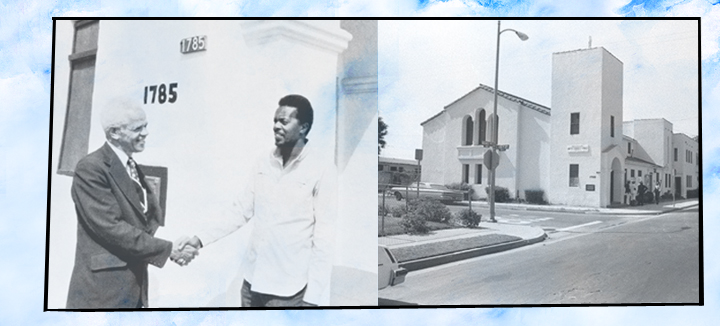

Left: Rev. E. Edwards and Horace Tapscott in front of Immanuel United Church of Christ 85th and Homes - Los Angeles. Photo by Michael PruessnerRight: Immanuel United Church of Christ 85th and Homes - Los Angeles. Photo by Mark Weber

Left: Rev. E. Edwards and Horace Tapscott in front of Immanuel United Church of Christ 85th and Homes - Los Angeles. Photo by Michael PruessnerRight: Immanuel United Church of Christ 85th and Homes - Los Angeles. Photo by Mark WeberTapscott, born in Texas, moved to L.A. with his mom in the early ‘40s. He began studying music in high school, initially the trombone, and came up with guys like Eric Dolphy, Don Cherry, and John Carter. Tapscott joined the Air Force and played with their band for a couple of years on ‘bone, baritone sax and piano. When he got out in the late ‘50s he went back to L.A. and played with various people, ending up in Lionel Hampton’s touring band. The way it’s told, he caught Coltrane’s November 1961 residency with Dolphy at the Village Vanguard, and began to imagine new sonic possibilities. He was also interested to learn that while Coltrane and Dolphy were both signed to major labels, neither of them had any dough to show for it. Both of these revelations were instructive.

Returning to L.A., Tapscott decided to get his own thing going. Although he still played the odd live gig with local bandleaders, his main focus became creating an organization to explore, celebrate and advance the vernacular sounds of South Central, Los Angeles. Historical details differ a bit, but the initial core of Tapscott’s scene were trombonist Lester Robinson, alto saxophonist Jimmy Woods, bassist Dave Bryant (all of whom had been Tapscott’s bandmates in Gerald Wilson’s Orchestra) plus singer/pianist Linda Hill. They jammed ceaselessly both at Linda’s house and in Tapscott’s garage, eventually introducing arrangements of traditional spirituals and works by African American composers into their repertoire. At some point in 1961, they coalesced into a group called the Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (P.A.P.A.). In 1963, when he decided to start doing community outreach and teaching, Tapscott formed an umbrella organization, the Underground Musicians Association (UGMA). This activity was somewhat parallel to what Muhal Richard Abrams was doing in Chicago (forming the AACM in 1965, after founding the Experimental Band in ‘62), Leroi Jones’ work in Harlem with BART/S (itself an outgrowth of the Umbra Poets Workshop), and later the Black Artists Group (BAG) in St. Louis. But one of the main tenets of the UGMA was to create a scene that would help the area’s youth to keep out of trouble by teaching them music and getting them to play as members of P.A.P.A. Over 300 players passed through the Arkestra’s ranks through the years, even though they didn’t have a recording released until 1978.

The Arkestra started to become well known inside the community during the Watts Rebellion in August 1965, when they drove through the neighborhood playing music from the back of a flatbed truck in an attempt to calm things down (although local police reportedly drew guns on them in an attempt to get them to stop). The UMGA’s outreach program grew larger after this, but the Arkestra’s music remained largely undocumented. There was supposed to have been an early ‘60s small band session cut for Contemporary, but it was nixed by Tapscott. His first significant mark on record is Sonny’s Dream (Birth of the New Cool), a 1968 Prestige LP featuring Tapscott’s compositions and arrangements (although the band of Arkestra players he and Sonny Criss assembled for the date were summarily replaced by the label, apart from drummer Everett Brown Jr.)

Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, June 28, 1981. Photo by Mark Weber

Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, June 28, 1981. Photo by Mark WeberThe first album released under his name was an uncharacteristic foray into small ensemble free jazz — 1969’s The Giant Has Awakened by the Horace Tapscott Quintet (recorded as part of a brief L.A. push by Flying Dutchman, which also included Stanley Crouch’s Ain’t No Ambulances for No Nigguhs Tonight and Flight for Four by the John Carter/Bobby Bradford Quartet). Tapscott also took part in a session, guesting with the Carter/Bradford Quartet, for a track on the Head Start compilation and a follow-up album to Giant was supposedly begun before relations with Bob Thiele (the head of Flying Dutchman) ran into trouble. Although Taspcott has had little good to say about The Giant LP, it’s a classic and important document of the L.A. scene in the late ‘60s. The quintet is a potent, boiled-down version of the Arkestra during the period that saxophonist “Black Arthur” Blythe was its musical director (as an aside, it’s worth noting that Blythe was not the same “Black Arthur” who played with Sun Ra, despite rumors to the contrary). The music on The Giant is a great loose blowing session with lots of free jazz highlighting and features the debut recording of Tapscott’s best known composition, “The Dark Tree.” In this period, Tapscott also worked with Elaine Brown, a singer/activist who would become the chairperson of the Black Panther Party in 1974. Tapscott and the Arkestra provided the music for Brown’s two LPs Seize the Time (Vault, 1969) and Elaine Brown (Black Forum, 1973).

It was around 1973 that Tapscott changed the name of the UGMA to UGMAA — Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension). This had to do with the fact that the organization was increasing its focus on non-musical arts — dancers, writers, painters and others were all encouraged to join in building up the community. ‘73 was also the year when the Arkestra began their regular monthly gig at Rev. Edgar Edward’s Immanuel United Church of Christ, where they played the last Sunday of every month until 1981. These concerts became legendary throughout Southern California, drawing a variety of listeners who would generally not be found visiting Watts. One of the people drawn to the scene was German ex-pat Tom Albach, who helped out various members of the Tapscott circle and eventually founded Nimbus Records to document their music. Between 1978 and 1984, Nimbus released 22 LPs documenting various facets of music created by Tapscott and his crew.

As interest in spiritual jazz has blossomed, some of these albums have gotten rare as shit. So it’s cool that Honest Jon’s subsidiary label, Outernational Sounds, has arranged to reissue some, including one that has only been on CD previously. The first batch is as follows.

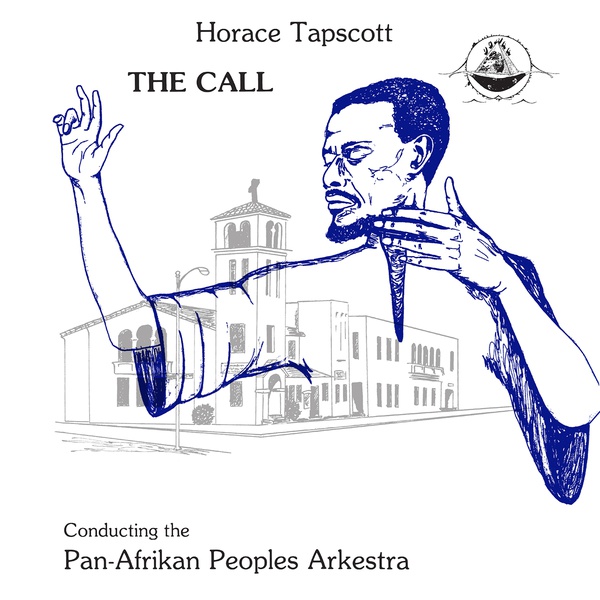

Horace Taspcott Conducting The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra — The Call (OTR 009LP, LP)

Horace Taspcott Conducting The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra — The Call (OTR 009LP, LP)The first released session by the P.A.P.A. was recorded at a couple of studio sessions (at Hollywood Sage Sound and United Western) in April, 1978. The ensemble is large, 15-16 pieces including bassist/tuba player George “Red” Callender who’d started playing in the Swing era (and would go on to work with flautist, James Newton). The overall sound of the four tracks is soulful and contemporary, and fairly avant in spots. The title track (written by trombonist, Lester Robinson) is a long flowing piece built on big modal blocks laced with avant outcroppings. “Quagmire Manor at Five AM” (music by altoist Michael Session, lyrics by vocalist Adele Sebastian) starts with King Pleasure-paced vocals about the band’s home base, then shifts into Tapscott’s fast keyboard dissonances and split tone sax that is more bar-walker than Ayler. “Nakatini Suite” is a tune by Cal Massey first recorded by Coltrane in ‘59 as “Nakatini Serenade,” with a vaguely African theme and sections of harmonic tension that make me think of Oliver Nelson’s arrangements. Last up is “Peyote Song No. III” (by reedman Jesse Sharps, who took over as musical leader after Blythe split for NYC in ‘73). Like many peyote trips, its structure is built around a central sort of swirl, and the sound of strings can be prominent.

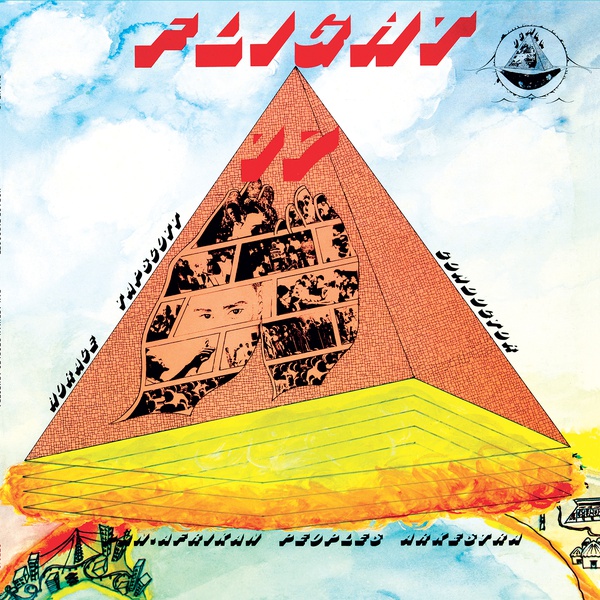

Horace Tapscott With The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra — Flight 17 (OTR 010LP, 2LP)

Horace Tapscott With The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra — Flight 17 (OTR 010LP, 2LP)This reissue includes the extra tracks that were originally available on the 1997 CD release. The first five tracks came from the same session that produced The Call. Flight 17 was actually the first release on Tom Albach’s Nimbus label (the name change to Nimbus West came later), but I’m listing it second since the extra tracks were recorded later. The two opening pieces here — “Flight 17” and “Breeze” — were both written by a local teenaged pianist, Herbert Baker, who died in 1970. His compositions mix a kind of cinematic melodicism with a bit of a Sun Ra feel (although whether that was Baker’s doing or Taspcott’s is unknown.) Certainly Flight 17, as presented, would fit in that other Arkestra’s songbook, mixing nostalgia, neo-classical ornamentation, space age logic and rhythm-driven freak scrambling into a strange and fascinating whole. “Horacia” (by bassist Roberto Miranda, who had not yet recorded with P.A.P.A. and was still primarily associated with Vinny Golia’s scene in West L.A.) has a very friendly Latin lilt and uses the wooden flute as a doorway to the unknown. “Clarice” (by Jesse Sharps) starts in an almost west-coast-cool style before ratcheting up into very urban sax turf. And ”Maui” (by bassist Kamonta Lawrence Polk) refrains from the exotica implied by the title and goes for a groove of odd bass moves blended with outside harmonics. The two live tracks that make up the second LP are recorded by a smaller, different band (with Miranda on bass and “Sabia Matten” — better known as Sabir Mateen — on tenor). These two tracks are rangy and loose. The one called “Coltrane Medley,” feels a bit more like a tribute than a medley. Adele Sebastian sings lyrics about JC and being free and later Tapscott runs through some Coltrane leads (although not all are Coltrane compositions), but the overall effect will make Spirit Jazz types tweet in ecstasy. “Village Dance Revisited” although uncredited, seems like a version of a Mateen composition P.A.P.A would release on record soon after. Lots of hand percussion and vicious arco bass sections are its hallmarks.

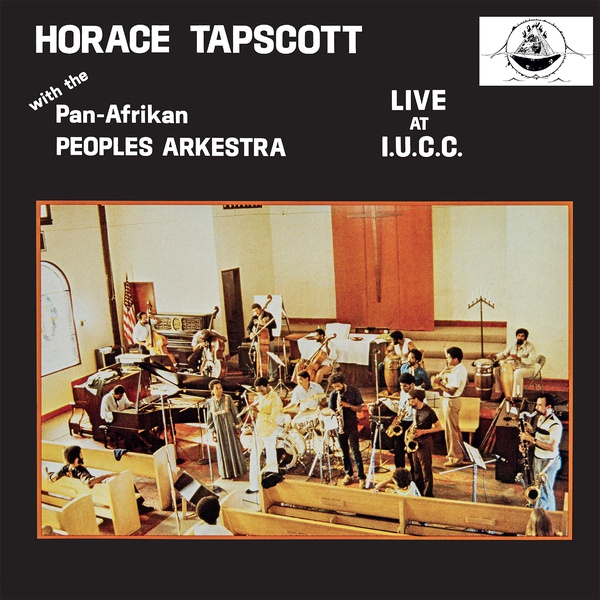

Horace Tapscott With The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra — Live at the I.U.C.C. (OTR 007LP, 2LP)

Horace Tapscott With The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra — Live at the I.U.C.C. (OTR 007LP, 2LP)This sprawling live session, recorded between February and June, 1979, on stage at the band’s regular “last Sunday” gig, at the corner of 85th and Holmes in the heart of Watts, is my favorite album cut by P.A.P.A. Tapscott loved the boomy sound of the room, and even though there’s only one bassist playing at a time (unlike on some of their other records) the music is equal parts grounded and ecstatic. Of the six tunes, two are by Jesse Sharps. “Macrame” is classic groove-and-solo formalism mixing clots of rhythm with free-flowing reed action. “Desert Fairy Princess” was written for P.A.P.A’s flautist/vocalist Adele Sebastian, who was not present on these dates, but who recorded it as the title track of her 1981 LP. Here, the dusty, slithering flute melody is played by Kafi Larry Roberts. Two other tracks were written by Sabir Mateen. “Noissessprahs” is a long bundling collection of sax tangles with some excellent soloing by Sabir that gets about as far out as the Arkestra ever did. “Village Dance” is a longer, more groovulating version of the bonus track from The Call, with heavy flute presence. Tapscott wrote one track, “LTT,” which has an odd cha-cha sort of time base to its central vamp although the horn parts are not the sort that would put a smile on Ricky Ricardo’s face. “Future Sally’s Time” is credited to Arthur Blythe and thought-criminal Stanley Crouch (probably penned when Crouch was still drumming for David Murray) which is something of a showcase for Tapscott, beginning with ragtime mutations and then expanding through the music’s style histories (at least, in a way). The final track is the so-called Negro National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a secular carol, written by the Johnson brothers (one of whom was the head of the NACCP for many years). It is scored here for piano and voices (presumably voices from the congregation/audience.)

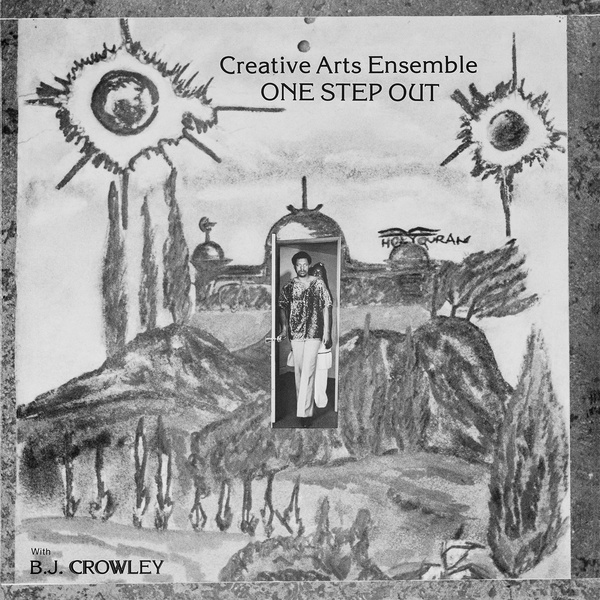

Creative Arts Ensemble — One Step Out (OTR 005LP, LP)

Creative Arts Ensemble — One Step Out (OTR 005LP, LP)The debut album by the Creative Arts Ensemble was recorded and released in 1981. It was among the first batch of Nimbus albums to emerge in the wake of Tapscott’s illness (a brain aneurism), as key players began to drift away from the dormant mothership. Some (like Jesse Sharps and Michael Session) joined the military, others (like Mateen) left for the East Coast. The future of P.A.P.A. an institution was unclear, but the music went on unabated. The Creative Arts Ensemble was a tentet assembled by pianist Kaeef Ruzadun. It featured members of the Tapscott organization, apart from baritone sax player Jeff Clayton (an active L.A. session guy) and bassist Henry Franklin (who’d emerged with the John Carter/Bobby Bradford group and was the house bassist for the Black Jazz label). All four tracks were written by Kaeef and some feature (very June Tyson-like) vocals by his sister, B.J. Crowley. Kaeef’s piano work is somewhat similar to Tapscott’s, although it’s blockier and less dissonant, perhaps replacing Tapscott’s Monk influence with one more pointed towards McCoy Tyner. The pieces are all very much in pure spirit jazz mode, and bear striking similarities to work by Sun Ra’s Arkestra on both the title track and (especially) “Stars in Light Year Time.” One Step Out is a very solid listen, no matter your inclinations.

Jesse Sharps Quintet & P.A.P.A. — Sharps and Flats (OTR 004LP, 2LP)

Jesse Sharps Quintet & P.A.P.A. — Sharps and Flats (OTR 004LP, 2LP) Reed player Jesse Sharps became the musical director of P.A.P.A. following Arthur Blythe’s departure. He held this chair until he joined the army and was shipped off to Germany in 1979. After a time in Europe he returned to L.A. and put together this band, combining players who had been part of his old scene with new faces. Sharps wrote all the tunes, apart from one “As a Child” by Tapscott, and that includes the P.A.P.A. track that’s an out-take from the I.U.C.C. set. The quintet plays in the darker range of the spirit jazz continuum, with much more hard-edged sax and a rhythm section that drives more than it dances. The take here of “Macrame,” for instance, has a kind of hard bop compression absent from the earlier version, which allows everything to unwind with stoned and languid grace, even though it still maintains a melodic vibe that is pure Pharoah Sanders. The P.A.P.A. track (which does not seem to feature Sharps as a player) has a somewhat loopy pulse that suggests its title (“McCowksy’s First Fifth”) may have to do with a local character’s drinking habits, or not. Regardless, it provides a nice work-out for Tapscott, Mateen, flautist Aubrey Hart, and other Arkestra players, ending things on a high and spirited note indeed.

You have been warned!

—Byron Coley, April 2019

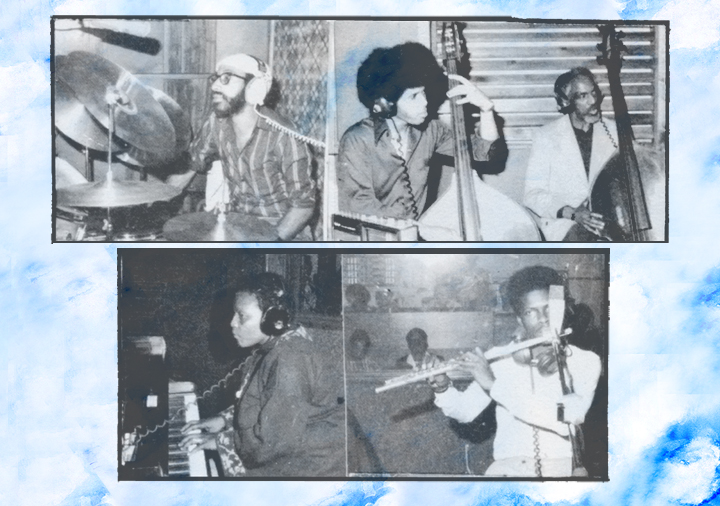

Taken from the sleeve of Outernational Sound’s Flight 17 reissue. Illustrations & Designs by Michael D. Wilcots

Taken from the sleeve of Outernational Sound’s Flight 17 reissue. Illustrations & Designs by Michael D. Wilcots