CLICK HERE TO PURCHASE Oliver: Stone UnturnedLionel Bart's musical, Oliver!, made its London debut in 1960 and was an instant success. David Merrick brought it to Broadway in '63, where it was equally popular, and Carol Reed's 1968 film version won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Many of the show's tunes were sung by young people, and the material was quite treacly. With this combination of factors, you'd think performers named Oliver would have ditched their real name in droves. Still, a North Carolina-based singer named Bill Swofford began using it as his soubriquet after attempts at stardom with bands like The Virginians, and The Good Earth Trio failed to gain traction. Swofford's lousy version of “Good Morning Starshine” (one of the shittiest songs from Hair) got to #3 on the U.S. singles charts in July '69, paving the way for the definitive version of the tune (as recorded by Andy Williams and the Osmond Brothers) that same year. Some people have reported that Oliver's version of “Starshine” was as crucial as the Beatles were to catalyzing Charles Manson's “Helter Skelter” philosophy, but only Ed Sanders knows for certain.

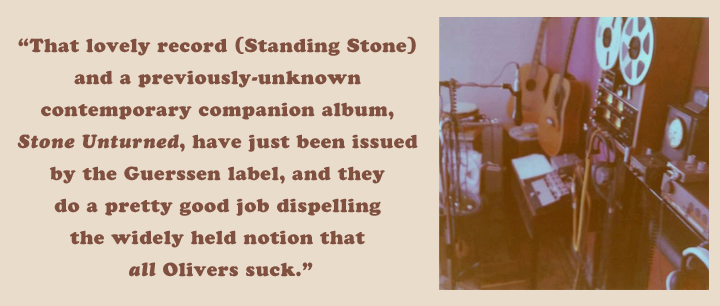

Even though there are over 100 artists on Discogs who record simply as “Oliver” (versus a mere dozen variations on Artful Dodger and just six Fagins — two more names from Bart's playbook), the name is not one that automatically excites seasoned record shoppers. There is, of course, an exception which proves this rule and that is Oliver (Chaplin) who released the Standing Stone LP on his own OLIV label in 1974. That lovely record and a previously-unknown contemporary companion album, Stone Unturned, have just been issued by the Guerssen label, and they do a pretty good job dispelling the widely held notion that all Olivers suck.

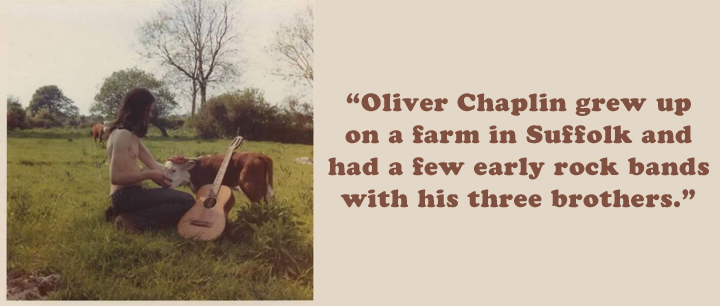

Oliver Chaplin grew up on a farm in Suffolk and had a few early rock bands with his three brothers. His family moved to a farm in southwest Wales in '65, where he continued to play music, although more often in a völk style. He went off to University in Essex in '68 and when he came home, he found his brother Giles had moved into a nearby tumbledown mansion, which he was busy turning into a hippie hang-out. Oliver and Giles began regular instrumental jam sessions at the mansion, and also played at local venues, doing long semi-abstract dual guitar workouts using homemade fuzz and effects boxes.

Meanwhile, another Chaplin brother, Chris, had moved to London to work as a mastering tech for the BBC's Transcription Services. Sometime in '72 he brought a Teac 4 track with him when he came home for a visit, and Oliver began screwing around with it tout de suite. Over the course of '73 Oliver put together the 17 songs that comprise Standing Stone. He recorded the material with just his voice and guitars, but it's assumed Chris added more effects, phasing and whatnot, when the tapes were turned over to him for mastering. There's certainly more going on throughout the album than basic singer-songerwriterism.

The music on Standing Stone is a totally weird blend of elements. Chaplin says the only real influences on its sound would be Robert Johnson, Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley, but I hear a lot other things going on. For an ostensible solo album, the record's sonic range is quite expansive. There is certainly a blues element that pops up a lot, but the only song that really calls up Robert Johnson is “Freezing Cold Like an Iceberg,” which is also reminiscent of “China Pig,” Beefheart's surreal-roots duet with Gary Marker from Trout Mask Replica. This tune is why Beefheart's name gets thrown around when people try to describe Standing Stone. There's not another track that really vibes Beefheartly, although the strangely squozed guitar parts on “Cat and the Rat” do illustrate a Beefheart line from “Sam with the Showing Scalp Flat-top” regarding “opaque melodies that would bug most people.”

More often, the comparisons I'd draw are to more well-known folkies and bluesers. “Off on a Trek” is a fast trad ballad in Ralph McTell's range. “Trance” has the jittery logic you might get if you dosed Duster Bennett with acid. “Royal Flush” toys with Renbourn's medieval instrumental approach. “Instamatic” and “Tricycle” use some of the same Ragtime/Piedmont style fusions as Stefan Grossman. “Motorway” feels as though it's an attempt to actually merge The Two Sides of Tony McPhee. “In Vain” would fit easily onto Clark-Hutchinson's A=MH2. And so on. The hops between styles are not gigantic, but they’re give the album a quietly shocking edge.

Which is not to infer Standing Stone is mimetic in any sense. Its overall heft is weird-and-original-as-hell, but there are individual elements that seem familiar for one reason or another. That said, it's a magnificent and perplexing album. Pressed and released in an edition of 200 copies in 1974, it was beneath the radar of most everyone, except for John Peel, who is the only known BBC DJ to have played the album, despite Chris Chaplin's connections. There was talk of Virgin Records helping to distribute the LP, but that never happened. Subsequently, Oliver took off to trek around Europe, satisfied that he'd at least gotten a record into the hands of friends and family members who were interested. When he returned home, he was on to other pursuits.

That's where things stood for 15 years. In the meantime, record collecting moved from doo wop and rockabilly into garage and psych. The first wave of British psych sound recycling had started in the early '80s when Malcolm Galloway's Psycho label and Phil Smee's Bam Caruso imprint began translating the Freakbeat codex and issuing comps like Perfumed Garden and Rubble. By the end of the decade, a new generation of hunter/gatherers had begun to serious catalog the British private press universe, from the thuggery of the Dark to the sweetness of Stone Angel, as well as the diverse offerings of private and vanity labels like Holyground and Deroy.

The first time I read about Oliver's album was in the early '90s in some rare record catalog, maybe the insane one that was put together by Stephen Smith (who went on to found the Kissing Spell label.) Whoever was writing about it made Standing Stone sound like another one of those essential albums you'd have no luck tracking down. Ever. I was hoping for a decent boot, when David Wells announced he'd be doing an authorized reissue as the debut release on his Tenth Planet label. This was excellent news, and the Oliver album proved to be one of the few that actually lived up to the hype. Although I quibbled with some of descriptive specifics, Standing Stone was definitely a unique and fucked-up charmer. Wells announced he'd soon be doing a CD version with six previously unreleased tracks from the same sessions. And even though I'm not a “CD guy,” I was curious to check it out. Sadly, the eventual CD issue offered no extra tunes or explanations of where they'd gone. Not surprising, but a bummer.

Now, after another thirty years, Guerssen has fulfilled Tenth Planet's promise (and then some), pairing their reissue of Standing Stone with a new 13 track LP of contemporary material entitled, Stone Unturned.

Presumably the six tracks mentioned by Tenth Planet are amongst these new ones, and as with most albums of leftovers, there are two distinct categories of tunes included. There are several which feel more “produced,” and were probably weeded out when the final track selection for Standing Stone was being made. The others are contemporary, but much less formal, feeling either like sketches for tunes or instrumental pieces in the vein of what Oliver is described as playing live. The overall heft of the tracks on Stone Unturned resembles the transitional UK/CA blues John Mayall was doing in the Blues from Laurel Canyon/Turning Point era as well the Danny Kirwan-ascendant phase Fleetwood Mac went through in their Kiln House/Future Games period. But there are other forces at work as well.

“Tantalize” sounds like Wizz Jones sitting in with Tyrannosaurus Rex. “Two Guitars” is an instrumental with a bit of McTell's melodic flair. “Little Woman” is a stark but cutting rocker with the same edge as the Mike Wilhelm/Loose Gravel version of “Styrofoam.” “Noise in the Night” is almost like one of Zappa's blues-knock-offs, and so on. There are also more vocal nods to Marc Bolan, and even one tune (“Mesmerizing”) that sounds a little like Cat Stevens being attacked by a wah-wah pedal. Stone Unturned has plenty of cool moments, but the material is not nearly as consistent as on Standing Stone. But if you really dig that one, you'll def get a kick out of the other. It reminds me of the 3LP version of Skip Spence's Oar. The additional material is not really on a par with the first batch, but the first batch is so insanely good, a second helping will be equally delicious to listeners who have thoroughly ingested the original.

To quote Lionel Bart's pathetic orphan, “Please sir, I'd like more.” For once, I actually agree with the little twerp. You will too.

—Byron Coley